After writing about why Romanization is bad for Korean (in my previous post), today, I’m going to explore the other side of the argument. This post will explore when to use Romanization for language learning.

To be clear, my position on Korean hasn’t changed: you should not use Romanization to learn Korean. Hangul is too easy to learn. But what about other languages?

I believe that using your native script (like Hangul for me, or Romanization for an English speaker) can be a useful tool in very specific situations. Today, I’ll explore why.

Languages Where Learning to Read Is Challenging

My strong advice against Romanization is specific to Korean because Hangul is so easy to read. This is not true for all languages. Using your native script can be helpful, especially when learning to read is a time-consuming process.

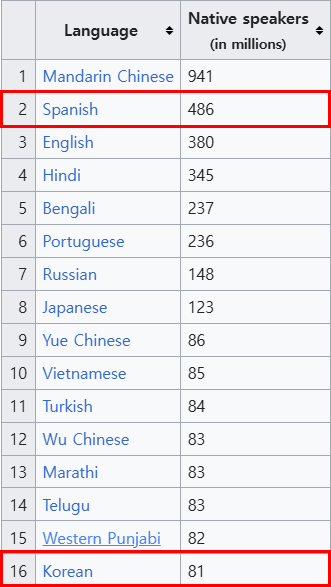

I’ve studied Japanese, Chinese, Thai, and English.

- Japanese and Chinese use characters (Kanji and Hanzi). If you come across an unfamiliar character, you simply can’t read it. It’s said that Chinese people use around 3,500 characters in daily life. Japanese, which also uses Hiragana and Katakana, still requires you to learn over 2,000 characters to read and write.

- Thai has 44 consonants, 32 vowels, and 10 unique numbers. Even after memorizing these, you’re only just beginning. Each consonant and vowel falls into specific categories, and various rules apply depending on their combinations. Plus, there are five tones. I studied Thai script with a native teacher, but I still can’t read it.

- English, with its 26 letters, seems simple. However, the lack of consistent rules makes it difficult. There are countless examples like “yes” and “eyes” or “thought,” “tough,” and “dough,” where the same letters are pronounced differently.

In all these cases, learning to read is a major roadblock that can take months or years to overcome.

Reading First vs. Speaking First: A Key Part of Language Learning

For most learners, the primary goal is speaking. This creates a conflict: the reading vs speaking first language learning debate.

- Reading First (The Korean Method): I strongly recommend that beginners in Korean learn Hangul first. Why? Because you can learn to read it in a few hours. Investing this tiny amount of time unlocks your reading ability, which will greatly benefit your overall Korean learning journey. This is precisely why Romanization is bad for Korean—it’s a crutch you do not need.

- Speaking First (The Thai/Chinese Method): For the languages I studied (Thai, Chinese), the “reading first” approach was impossible. It would take too long. My primary goal was to converse with native friends, so I focused on speaking first.

This is the only situation when to use Romanization for language learning: as a temporary tool to learn speaking when the writing system is too difficult to learn quickly.

How to Use Romanization as a Learning Tool (My Method)

So, how do you use Romanization as a learning tool without developing bad habits? I focused on speaking first. During this time, writing foreign words using Hangul (my native script) was incredibly helpful.

When learning foreign languages, I frequently used the Anki app. As shown in the image above, I wrote Thai pronunciations as closely as possible in Hangul on flashcards. It didn’t matter if it strayed from standard Hangul rules.

Of course, it’s impossible to represent the pronunciation with 100% accuracy. I wrote it in a way that would help me (and only me) recall the correct Thai pronunciation. If English were my native language, I might have written it as “P-eom R-eom,” for example—something only I would understand.

The Most Crucial Point: Native Audio

One crucial point here is the use of native audio. This entire “speaking first” method fails without it.

I stored audio for every flashcard, asking native teachers or friends to record it for me. I would read my Hangul “Romanization” while repeatedly listening to the native pronunciation. This allowed me to practice Thai pronunciation even with imperfect transcriptions.

This is the correct way to use Romanization as a learning tool. The transcription is just a visual cue to help you recall the sound. The native audio is the “ground truth” that trains your mouth and ears. Without using Anki with native audio, I would have just been learning to pronounce Thai with a Korean accent. This is the real secret to when to use Romanization for language learning: only as a temporary bridge, and only when paired with authentic audio.

➤ This philosophy—the importance of native audio—is why all the audio in the Podo Korean app, designed for serious learners, was recorded by me. You can save your favorite sentences as flashcards and practice them repeatedly with audio.

Although AI technology has advanced, I’ve found that AI-generated pronunciations can still sound unnatural. As a native teacher, I prefer to wait until AI audio improves to the point where it sounds as natural as a native speaker before using it extensively.